“Total chaos”.

That was how the Devil’s Burdens relays was described to me, but it contained a caveat…

“…it’s just brilliant.”

I was reminded of those words as, on leg three, my partner David and I flew helter-skelter down into Mapsie Den and into the natural amphitheatre created by the trees. Ahead of us, the changeover for leg three to four was marked by a wall of vest-clad individuals, all bouncing on their toes to stay warm on that damp January day.

A steep right-hand turn threw us into this venue and a marshal at the corner cried: “What’s your number?”.

“154”, I rattled through sharp breaths. He then bellowed: “ONE-FIVE-FOUR!” to the waiting runners as we sprinted towards our purple-clad Ochils leg four runner. As fast as lightning, David handed the sheet of hole-punched paper to Lee who disappeared back up the way we had just come to tackle the 5.8km/390m final leg.

This is the Devil’s Burdens, Scottish hill racing’s only relay race.

Almost exactly an hour before, Dave and I were stood in a large bomb hole just above the Fife town of Kinneswood, waiting for Adam and Brian, our fellow senior men’s Ochil Hill Runners, to pass us the punched sheet for our leg.

The Burdens is a buzzing event, with around 1200 runners (according to some reports), making around 200 teams of six in a 26mi² area of the Lomond Hills in Fife. The three main summits of East and West Lomond and Bishops Hill are criss-crossed over four legs – one trail, three hill, two of which are paired.

We watched from our small knoll towards a gorse-flanked bump just 500m away, watching for purple vests to appear. Behind us, dozens of other runners and spectators stood waiting for their changeover.

The weather changed with every minute: the crags below Bishops’ summit came and went as clag enveloped and then released them constantly, and all the while rain and wind cascaded over Loch Leven towards us.

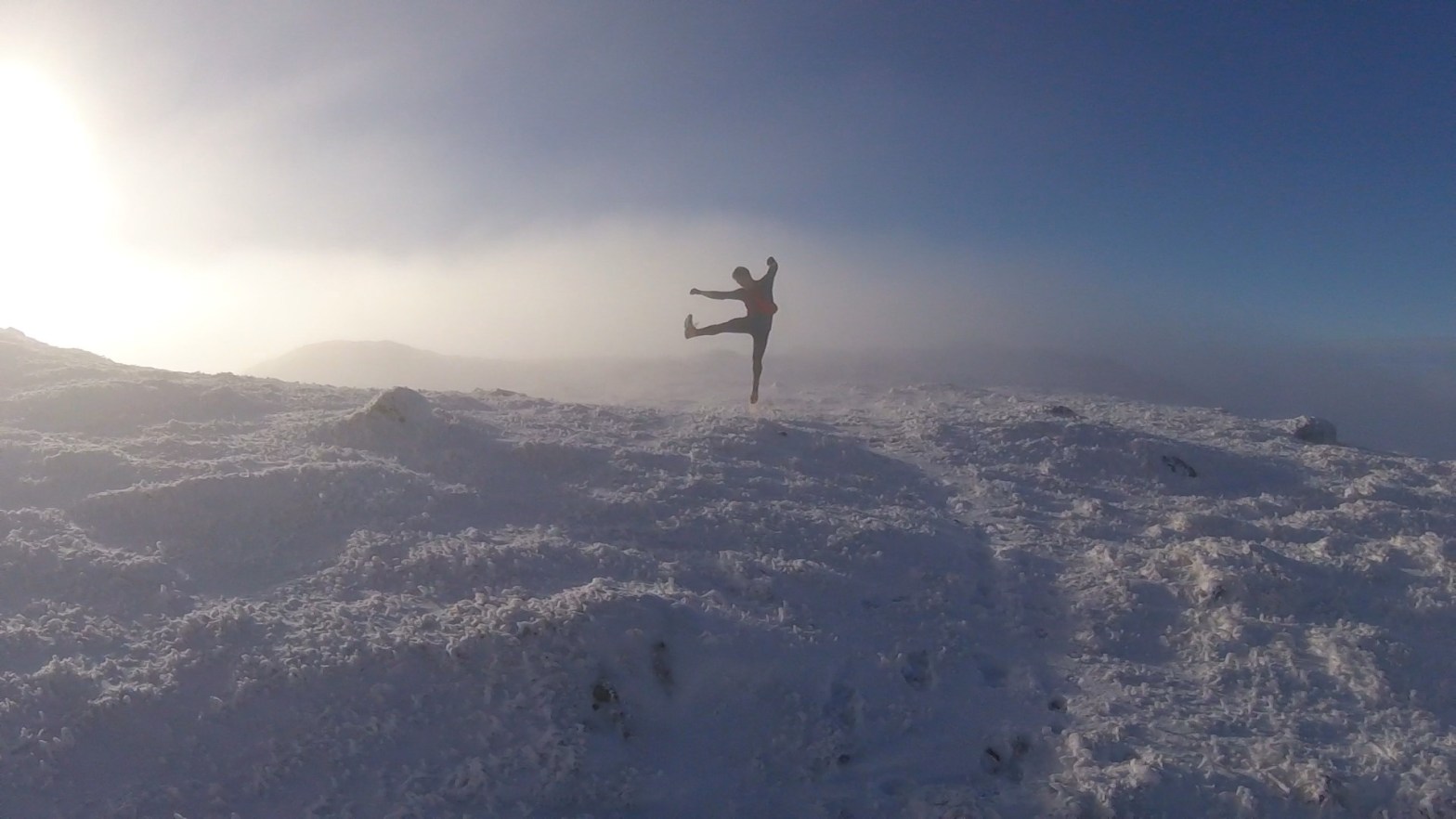

I saw a great tweet from Jonny Muir describing the scene of “loons” streaming through the hills in “little else than shorts and a warm hat”. That was us – minus the hat, but staying civilised with a vest over a t-shirt. After all, it was “fair windy up top, aye”, as any other runner who had just finished leg two would say.

We stood next to Grant and Gary, the V40 OHR leg three runners who – in the spirit of healthy intra-club competition – we wanted to beat.

At 12.05, purple appeared on the horizon and Dave and I dashed into the changeover. Adam came fleeing over the crest of the hill into the hole where we stood and we took up the slip of paper we had to punch at the checkpoints.

“COME ON OCHILS!” he screamed at us as we sprinted away. Immediately, though, the sprint turns into a hands-on-knees effort up Bishops Hill. Ahead of us, a steady stream of vests could be seen from the other leg three runners, most of whom’s leg one runner been set off at the earlier 09.30 start versus our 10.30 start.

Because of their size, larger clubs have sometimes several teams in each category, with the ‘second’ team heading off for the earlier slot. It was because of this arrangement we had some added motivation, passing some of the slower pairs on the mind-bindingly steep slope – averaging 40%, but with a solid section almost 50%.

We popped above the crags and started to head north-ish, and soon became swallowed in clag. With nothing to go on except our noses and a hazy knowledge of the land from a recce last week, we ploughed on.

“Does this feel familiar?”, David called, his voice distant in the wind. “I think so”, I mused. “We came up a different way last week.”

Soon, though, as always happens in poor visibility, you get the treadmill effect; you are running, but you aren’t really going anywhere. I pulled out my compass, which showed we were heading east, not north as we should.

“What do you reckon?”, Dave asked. And then I gave him that look that said, “Bugger”. “The path will probably bend round”, Dave posited. “True, either way, if we don’t hit checkpoint nine and start going steeply downhill, we know we’ve gone wrong.”

We continued and, sure enough, a moment later the path did bend round and the gate with the punch appeared. Punching the hole into the box labelled for nine on the sheet, we headed on.

As we ran along the path we quickly picked up speed, going into full steam train mode as we covered the ground to checkpoint 10. Nothing could hold us back: bogs? Straight through them. Mud? Dive down it. Rocks? Jump. We just kept running in this exhilarating dash across the hills.

We soon found a good pace that we could settle into equally, matching strides well on each landing. Being made of Old Red Sandstone, the mud turned to clay on the descent into Glen Vale, but with limbs everywhere we just careered onwards.

After hitting the tourist path for 1km or so, it was back up a steep grassy slope to just below West Lomond. At the point, we were covering the ground leg two had done in the reverse, so by now the ground was well-trod and muddy.

Because we had found a rhythm, we were slowly picking runners off, but it was unclear whether they were 09.30 or 10.30 starters – we took the overtakes regardless. We did lose a spot to some HBT runners as we contoured West Lomond to the penultimate checkpoint. A pair we had not seen was Grant and Gary, who had still been at the handover when we left.

By now, the clag had lifted entirely as we turned to face East Lomond on the long tourist path ahead. One runner commented to me in the hall later, “I hate leg three. That tourist path afterwards? It’s just rubbish. That’s not hill running. It’s trail!”

Whatever it was, it was fast, with the two of us settling into a leaning gait, legs turning in a full bicycle motion, arms propelling us forwards. Bizarrely, I got a 5k PB in a hill race, but it was all thanks to this slightly downhill (and subsequently VERY downhill) section of just over 5km to Falkland.

On the final left turn we entered the Mapsie Den, a brutal trail descent, legs getting a beating on the hard surface. As we descended through the final forest section, a purple vest came towards us. Nick, the V40 leg four runner for Ochil was on his way up.

In my haze of exertion, a small thought appeared: ‘Ah. Something’s gone wrong.’

We made the right-hander, sprinted to the changeover and let Lee loose.

When we could see properly again (our eyes being out the back of our heads as we sprinted down the last descent, legs and arms flailing everywhere), we looked to see who had arrived.

“Where did you go?”, Angela asked (she was running for Carnethy’s mixed team). “Grant and Gary came about three minutes ago!”

“Gah!” we exasperated, jokingly. Grant came up to us. “You must have passed us in the clag”, we said. “We dithered about quite a bit up there”.

It mattered very little. We were all grinning like mad, endorphins sky-high. We jogged easily back into Falkland and up into the woods to see Lee arrive. The wee soldier came flying into the finish straight, giving it all he had.

That’s what made the Burdens a special race – everyone was giving their bit for the team, and however well or badly the team performs, you all worked together to make the best of it.

In the end, that team effort made us 14th of 163 teams (the V40s came 11th, while the WV40s won their class! These V40s are quick!), and earned us a cup of soup and a roll. Get in.

What a way to start 2019! Next up is Carnethy 5 on February 9.

Thank you to Ochil Hill Runners for supporting the teams, to our club captain for building them, to the race organisers and marshals for their work, and to the Ochil Mountain Rescue Team for helping an injured walker on East Lomond during the race.